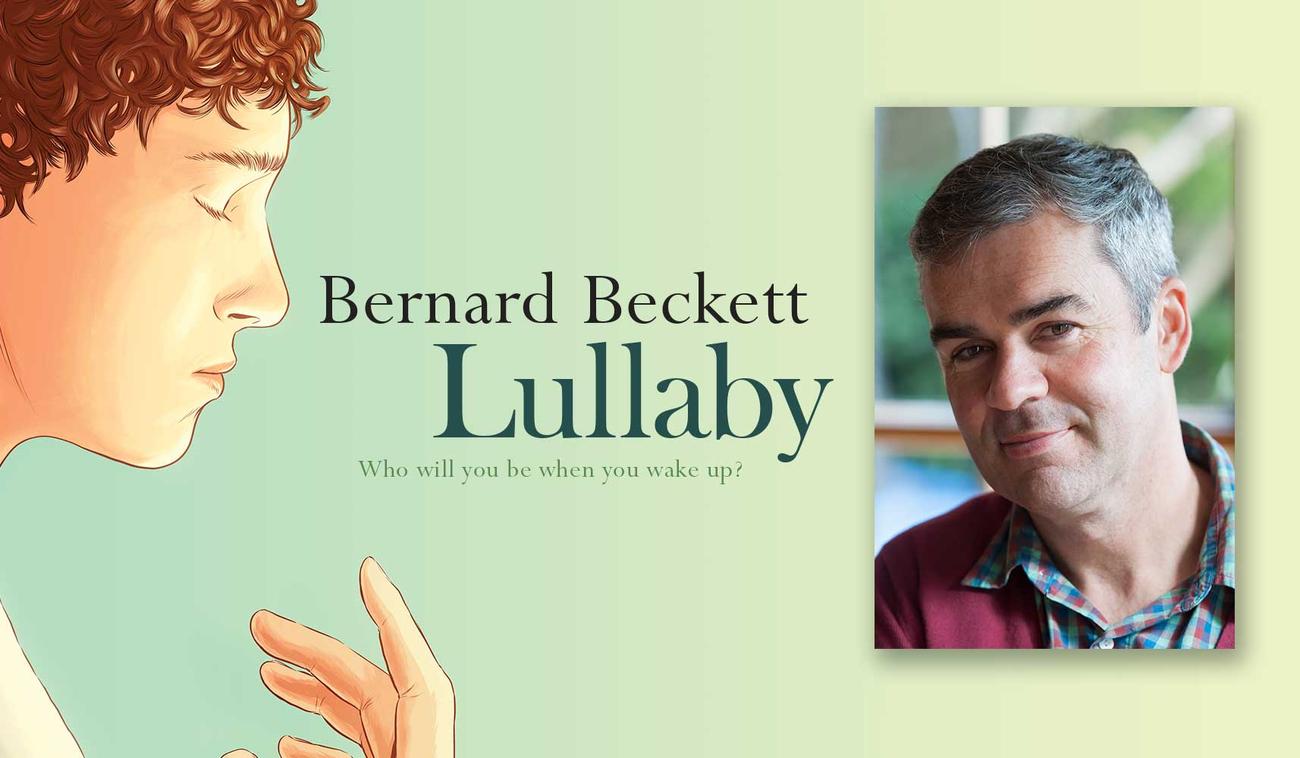

Bernard Beckett is the award-winning author of Genesis and August. His new and gripping psychological thriller, Lullaby, questions what makes us who we are.

Rene’s twin brother Theo lies unconscious in hospital after a freak accident left him with massively disrupted brain function. There is hope, though. An experimental procedure—risky, scientifically exciting and ethically questionable—could allow him to gain a new life. But what life, and at what cost? Only Rene can give the required consent. And now he must face that difficult decision.

Here Bernard answers some questions about the new book.

You’ve described Lullaby, Genesis and August as ‘thought experiments as novels’. While each book functions as a standalone novel did you also intend for them to work more cohesively, perhaps as a series of companion works?

Not in the sense that anything is added to the reading experience if you’ve read one of the others, but certainly they all catch me playing around with a similar idea—namely how to take an existing thought experiment and then give it life within the context of a narrative.

Why do you seek to challenge young adults and teenagers with these kinds of philosophical concepts? Where did that interest begin?

I think writing is always a little bit about writing for yourself. I find these ideas interesting, and so I enjoy exploring them in story form. I don’t consciously set out to raise them for a teen audience, that’s more a happy by-product of what is, to a large extent, my hobby.

What kind of feedback have you had from readers since the release of Genesis and August? Do readers often contact you looking for answers?

More often readers will want to share some of their own thoughts and ideas in this area, and in one case even sent me a book they thought I might enjoy.

You are the father of twin sons and your two main characters in Lullaby are also twins. How did this personal experience play into creating these characters?

I think personal experience gives you licence to create that aspect of the world in fiction. I’d be wary of writing about parenthood without first being a parent, just because I’m sure I would fail to capture its essence. Oddly, when I wrote Lullaby, I didn’t know my boys were identical, indeed we’d been told they probably weren’t. So, writing about identical twins almost gave a level of distance, and hence safety. Later, we discovered the boys are indeed identical, so life imitating art and all that.

Rene and Theo share many common traits and similarities, while also remaining distinctly individual. What do their differences represent? Could we label either Rene or Theo as a hero, and the other as a victim?

I think the most important thing the differences represent is the reaction to the other. I’m a big fan of the idea that in any family, or social setting, people will gravitate towards the roles left unfilled. I notice this a lot in the classroom. A student who, in one environment, will assume the mantle of leader, might take up the role of clown in another class, purely because the leadership role was already filled. A fascinating thing about identical twins is that the biggest environmental difference they experience is the existence of the other, and as each moves to fill their niche, the behaviours that go along with it become part of the environment within which the other is developing. The smallest initial difference can hence set off a cascade of individuality (here’s the place where I divert down the epigenetics path, but in the interests of brevity...). I’d not call either the hero, I don’t think, although Rene is clearly the protagonist, who faces the central moral choice.

Both Rene and Theo feel defined by people’s perceptions of the other. What do you think becomes of our identities when they are too tightly tied to another person?

As above, I think the interesting thing is the way our identity becomes, in part, a reaction to the person we’re close to, as much as anything. I think individuality is threatened only when one person cedes the right to make their own choices, although in Theo and Rene’s case, that never happens to them.

Lullaby is set almost entirely in one hospital room. Why did you choose this confined setting?

I write a lot of plays, and particularly enjoy real time, single-setting stories. There’s a kind of narrative immediacy that can’t be generated any other way, something to do with the way we’re not allowed to look away, and that any problems introduced to the story need to be solved before our eyes. Practically speaking, thought experiments often require a degree of exposition that is well served by combative dialogue. I pulled the same trick in Genesis, and probably need to retire it now.

Lullaby ends in an ambiguous manner, how do you hope your readers will feel when they turn that final page?

I hope it doesn’t feel too ambiguous, actually. I like the idea that there’s a moment required to let the pieces settle into place, and that when they do, for some readers there will be the sensation of seeing something from a perspective they hadn’t before contemplated. That would be an excellent outcome.

Is the ultimate goal of Lullaby (and your other ‘thought experiment’ novels) to assist the reader in handling these kinds of questions within their own realities?

I don’t think it is, no. Although I love philosophy, I think it’s best seen as an intellectual diversion, rather than a serious attempt to understand the world. My favourite philosopher, David Hume, wrote of how, immediately upon leaving his desk and joining his friends, his work appeared trivial. I think that’s a healthy perspective. Philosophy of this type is akin to puzzle solving. The big questions are best addressed through experience, I think. How to love, how to laugh, how to recover.

Are you likely to produce another ‘thought experiment novel’ soon? If so, any hints?

I’m just starting work on turning a play of mine into a novel, and there is a thought experiment element, although this time the key question is one of ethics rather than epistemology. It opens with a young man, chained to a wall, watching a woman being tortured.

See more about Bernard Beckett and Lullaby, download Australian curriculum teaching notes or read a preview here.

Explore more author interviews here.